Welcome to the new home of the Half-Brewed Blog!

As an academic navigating the endless sea of papers and research, I’ve often found myself brimming with ideas that never quite reached their full potential. These thoughts, partially-formed yet packed with possibility, are what inspired this space. The Half-Brewed Blog is a place to share those incomplete ideas—the ones that may not have a full conclusion but are enough to spark conversations and new ways of thinking. Whether you're a fellow student, a researcher, or just curious, I hope these half-brewed thoughts will inspire you to explore, question, and take the next step in your own projects.

“Gender Inclusion, Gender Exclusion, and Safety Delusions in Mexican Ska Festivals,” A Presentation for the SEM 2024 Annual Meeting

This post is more of an advertisement for my upcoming presentation at the Society for Ethnomusicology Annual Meeting. If you are interested in my work, please come and see what I have been working on recently. If my presentation at the conference led you here, please feel free to reach out or comment on this post to continue the conversation.

I am departing from my typical blog post to invite you to my upcoming conference presentation titled “Gender Inclusion, Gender Exclusion, and Safety Delusions in Mexican Ska Festivals.”

Once again, I am honored to present some of my recent work at the Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM) Annual Meeting. This presentation is part of the session on Gender Exclusion in Performance Spaces being held virtually on Thursday, October 17 at 12:30 pm EDT.

Gender Inclusion, Gender Exclusion, and Safety Delusions in Mexican Ska Festivals

Abstract:

Ska, a popular music genre originating in Jamaica, has idealistically served as a genre that creates spaces for inclusivity and unity. However, researchers have noted that these perceived utopian spaces did not prioritize the inclusion of women (Augustyn 2020, 2023; Black 2011; Sangaline 2022; Stratton, 2011). To further complicate ideas of utopia and unity, these studies of inclusion often exclude ska scenes outside of Jamaica, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Ska music has garnered immense popularity throughout the world, significantly in Mexico. In this paper, I investigate Mexican ska music festivals as a gendered space to address current questions in ethnomusicology regarding intersectionality and gender. I ask: to what extent are ska festivals in Mexico City and Tijuana designed to be inclusive or exclusive gendered environments? Is creating a safe environment a priority for festival organizers? Who is performing? Who is not? How are notions of masculinity like machismo reinforced to serve as barriers? How do women circumvent or operate within such structures of aggressive masculinity? Drawing from digital ethnography and fieldwork in Mexico City and Tijuana, I use these questions as a starting point to examine the similarities and differences of various festivals as they relate to issues of creating gender-inclusive spaces.

Looking into Florence B. Price’s “Five Folksongs in Counterpoint”

While de-cluttering my files, I stumbled upon this paper I wrote several years ago. This was written for a class I took on American Music the first semester of my PhD. This was a significant year in terms of reforming what I wanted as a researcher. During my first semester at UF, my professors provoked debate of equity in history. I questioned the canonization of art music in a way that I never had, and it changed my perception of what it means to write meaningful scholarship. I used this decolonization of my mind as a chance to write about an American composer whose work I was not very familiar with. Coming from a jazz background, I was interested in composers who drew from African American spirituals and the blues. In my undergraduate history courses, we had discussed William Grant Still, but I wanted to look into Black artists who were not found in the textbooks on Western art music that I had read. I considered a few composers before I read Rae Linda Brown's book The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. I listened to a few pieces and I knew I had to learn more. I appreciated the chance to write a paper that took me so far outside my comfort zone of jazz studies and popular music studies.

Florence B. Price is often cited as the first African American woman to have a large-scale work performed by a major American orchestra; an honor achieved when her Symphony in E Minor was premiered by the Chicago Symphony in 1933. She is also remembered for her art songs and spiritual arrangements. Much of the published attention surrounding Price is related to her symphonic, keyboard, and vocal works, perhaps due to the magnitude of the symphony being a “first,” the status of her Piano Sonata in E Minor as award-winning, and her vocal works’ attachment to Marian Anderson. Even though there has been a growing interest in Price’s work over the last ten-to-fifteen years, there is still relatively little written about her instrumental chamber works.

One reason for this neglect is the until recent scarcity of extant scores. While she received acclaim for her first symphony, her Sonata in E Minor, art songs, and spiritual arrangements, she struggled to get many of her works performed or published. Because of this, many of her works were not saved for posterity and have gone missing. Were it not for the 2009 discovery of a treasure-trove of scores in Price’s former home, and the University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections’ acquisition of Price’s papers (including journals and manuscripts), much more of Price’s music would have been lost forever.[1]

Among the recently rediscovered scores in the Florence B. Price collection is Five Folksongs in Counterpoint. According to the manuscript, the piece was completed in 1951, within two years of Price’s death, though it is unclear when each of the movements was written. In program notes for a score that was edited and sold by the Apollo Chamber Players, Price biographer Linda Rae Brown explained that the string quartet could have been started as early as the 1920s, and erasures on the score indicate that it went through at least one name change.[2] Since the piece was finalized so late in her life, it offers a perspective of what Price sought to convey in her music at the end of her career. The potential that it was composed over the course of thirty years (or completed and edited), makes Five Folksongs in Counterpoint an interesting piece in which to analyze Florence Price’s compositional style for chamber works.

The aim of this study is to review Five Folksongs in Counterpoint as representative of Price’s compositional identity and reflective of her intersectionality as a southern-born, New England Conservatory-trained African American woman. Rather than emphasize whether or not this represents an important piece of American music, I aim to see how this work can exemplify an individual Florence B. Price compositional style.

Five Folksongs in Counterpoint is a string quartet in five movements, each of which is based on a different folksong. Three of the movements are based on African American spirituals: “Calvary,” “Shortnin’ Bread,” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The original score shows that Five Folksongs in Counterpoint was once titled Five Negro Folksongs in Counterpoint but was likely changed with the addition of “Clementine” and “Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes,” two folksongs that are not of African American derivation.[3]

The use of spirituals was a staple in Price’s compositional oeuvre throughout her career, and the use of spirituals and spiritual-like melodies in her symphonies and piano works has been noted by several scholars.[4] When she attended the New England Conservatory as a teenager, she “had become familiar with the use of vernacular elements in serious composition through her studies with George Chadwick.”[5] It was at the conservatory that she likely studied the work of other composers that made use of African American folksong and spirituals in their work, notably Antonín Dvořák. Writing about Symphony in E Minor, Price’s first symphony which was written while she was a student, Rae Linda Brown notes that:

Both Dvořák’s and Price’s symphonies are in the key of E Minor and both works have subtitles that suggest the inspiration for their primary source material. Originally subtitled the “Negro Symphony,” Price’s work assimilates characteristic Afro-American folk idioms into classical structures. [6]

The influence of Dvořák has also been noted by at least one reviewer of Five Folksongs in Counterpoint who said it “evoked Dvořák’s famed ‘American’ Quartet.”[7] In his oft-cited article, “The Real Values of Negro Melodies,” Antonin Dvořák stated “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States.”[8] This call for an American nationalist musical identity resonated with Price whose compositional identity appears entwined with black nationalist ideals influenced by the New Negro Movement.[9]

The aspiration for cultural expression in perceived high art associated with the New Negro Movement may be the cause of the telling absence of blues influence in Price’s Five Folksongs in Counterpoint. Figures like Mahalia Jackson have shaped a tradition of substantial use of blues inflections when singing spirituals. This influence is so strong that Price’s relative absence in this instance emphasizes her individuality. It is also interesting that she avoided the influence of jazz given the time she moved to Chicago in 1927. In the late 1920s, Chicago was an important hub for jazz. Louis Armstrong was still based in Chicago and recording some of his seminal work with The Hot Five and The Hot Seven, and Jelly Roll Morton recording with his Red Hot Peppers. Given the city’s vibrant jazz scene at the time and Price’s commitment to including African American influences in her music, it is striking that Price managed to evade a more direct influence. While this shows her individuality, it may also be revealing of Price’s past and her intersectionality as a high-class African American woman. Today, jazz is seen by many as an intellectual music, but in the 1920s it was not seen as highbrow, and the genre’s history is rife with anecdotes of musicians—especially those with privileged backgrounds—who were discouraged from performing jazz. James DeJongh contextualized the view many African American elites’ of jazz and blues:

We may have to remind ourselves that Hughes’s identification of Harlem with jazz and blues, which now seems so natural—perhaps even a bit trite—was severely criticized by black authority figures and rejected in its own time… The spirituals had come to be accepted by the Negro elite as dignified and ennobling folk forms, but blues and jazz were embarrassing reminders of a status they were trying to escape.[10]

With its lack of blues and jazz characteristics, Five Folksongs in Counterpoint reveals that Price sought to elevate the spiritual and African American folksong through the lens of the post-Romanticism of western art music.

Florence Price attended the New England Conservatory from 1903 to 1906, a program that would encourage Price to use vernacular music when composing in the western art tradition. While Price was at the conservatory, it was headed by George Whitefield Chadwick, the institution’s third director who served that role from 1897 to 1931. At Chadwick’s direction, “the school continued to raise its musical standards to such an extent that it was ‘probably the most severe of any music school in the country.’”[11] As Rae Linda Brown noted,

Chadwick moved quickly to raise the academic standard of the Conservatory. He modified the curriculum from its earlier emphasis on singing and piano playing to one that stressed harmony, counterpoint theory and analysis, and composition. In keeping with Chadwick’s aim to establish a first-rate American music school, he developed his own harmony book, Harmony: A Course of Study (published in 1897), for class use. He explained, “I was ambitious to make the book a model of expression, most of the books on Harmony being more or less poor translations from the German.”[12]

Under Chadwick’s instruction, Price honed her compositional craft, and it was here that she created some of her earliest amalgamations of western art music and African American spirituals and folksongs.

The final movement of Five Folksongs in Counterpoint is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” This movement shows Price taking the iconic pentatonic melody, and masterfully developing it along with new material, and gradually building the intensity resulting in a powerful piece that is telling of Price’s various identities.

In the first thirty-two measures of this movement (example 1) each instrumentalist, in turn, plays faithful renditions of the melody for eight measures, starting with the cello playing in C, the viola a fifth higher—in G, the second violin a fourth higher in C, and finally the first violin playing a fifth above that. The cello plays the melody unaccompanied with all of the parts joining in measure nine as the viola takes the melody. A look at the score for the movement’s opening shows that the melody is not the only shared material. Comparing the parts, it is clear that Price has used the melody of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” as the basis for thirty-two measure canon capable of being repeated and still maintaining its cohesiveness.

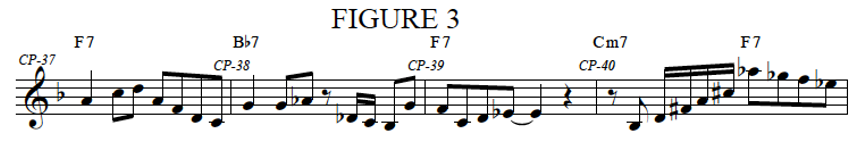

Example 1 - Opening melody

In the following section, Price departs from the familiar tune and instead develops themes and motives from the other parts of the canon, concealing melodic fragments of the original spiritual. Price’s choice to use her own thematic material as the primary focus for development rather than the melody of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” reinforces that this is not simply a rendition or arrangement of a spiritual, but a Florence Price composition based off of a spiritual. One example of thematic development of an accompanying part is in measures thirty-seven to forty-six. Price takes a motive heard first by the cello from measures eight to eleven, the viola in measures sixteen to nineteen, and the second violin in measures twenty-four to twenty-seven.

Example 2 - development theme

The original theme (example 2) starts with ascending eighth notes that imply a B7 chord on the last two beats of measure eight which lead to a descending E minor figure on measure nine. The motive includes a few characteristics that will be developed later in the piece: an upper neighbor figure followed by a descending line, an octave leap, and a descending sixteenth note figure ending on a quarter note.

Example 3 - Development (in red), Melody (in blue)

Example 3 shows exactly how Price uses this theme from measures thirty-seven to forty-six. It is first heard in full by the second violin player, playing in C major. Price then sequences the last two beats of the motive, moving down by step with each repetition. Two beats after the second violin plays the upper neighbor figure in measure thirty-eight it is played by the viola, followed by the cello in measure thirty-nine. Price uses this theme in every part, either in its entirety or fragmented until measure forty-six. Additionally, the original melody appears briefly in the cello part measure forty-five, and in the viola in measure forty-six.

Example 4 - Melody Return

In measure seventy-three the main theme returns—in C Major—in the second violin part, with segments of the melody also appearing in the cello part. The first violin plays a driving sixteenth note accompanying line, which seems to deceptively imply the ending of the movement at measure eighty. Price instead creates an exciting drive towards the end of the piece by having the first violin come in alone with a tremolo eighth note line while the second violin fragments the theme in a variety of keys including E-flat major and G-flat major. For the melody’s return, Price no longer adheres to the canon, and the other parts play tremolos of varying length (whole notes in the cello, quarter notes in the viola, and eighth notes in the first violin). Building even more, the first violin, in double stops, plays the melody in A-flat. The melody continues to cycle through different keys before finally settling back to C major at the end.

In this piece, Price reflects her own duality as an African American woman and a conservatory-trained composer navigating a musical idiom, western art music, that has a historic disregard for both Black and female composers. In a letter to Serge Koussevitzky, she explains her music as an attempt to do just this:

Having been born in the South and having spent most of my childhood there I believe I can truthfully say that I understand the real Negro music. In some of my work I make use of the idiom undiluted. Again, at other times it merely flavors my themes. And at still other times thoughts come in the garb of the other side of my mixed racial background. I have tried to for practical purposes to cultivate and preserve a facility of expression in both idioms, although I have an unwavering and compelling faith that a national music very beautiful and very American can come from the melting pot just as the nation itself has done.[13]

The instrumentation, the traditional harmony, the looseness of the form, the contrapuntal texture, and her sense of nationalism are all traits commonly associated with romantic composers and can be viewed as an expression of her identity as a conservatory-trained composer. Her dedicated use of the spiritual, “undiluted” in this case, as the source of national representation, an expression of her identity as an African American woman.

The written histories of western art music have, for the most part, reflected the works of white men. Reviewing the history of western art music specific to the United States, one finds a similar focus on white male composers. As with other countries with a colonial past, the United States has a history of not recognizing the achievements of marginalized people, and African American women in particular have been left out in several areas of American history.[14]Florence Price recognized the stereotypes she had to combat in gaining recognition for her work. After one of the most often-cited achievements of her career, the Chicago Symphony performance of her first symphony in 1933 as part of a program of all-African American compositions, several of the journalists who reviewed the concert either failed to mention Price, or mentioned her in passing between praise for the male contributors.[15]One problematic view Judith Tick points out in her analysis of turn-of-the-century views of women in music is that “musical creativity was… masculine by definition because it relied on male intellectual and psychological resources.”[16] In her article, Tick is responding to a book that was published during Price’s formative years and was written by a prominent music critic, not some fringe personality. Tick also explains ideas of femininity in regard to music:

Femininity in music was alleged to be delicate, graceful, refined, and sensitive. It was defined as the eternal feminine…(ewige weibliche)… Through 1900 the aesthetics of the eternal feminine in music included both form and style, as well as emotive content… Vocal music was the essence of ewige weibliche because it “appeals more directly to the heart.” Since harmony and counterpoint were “logical,” they were alien to femininity.[17]

Florence Price spent her career fighting these preconceived notions of her music. In 1943, Price sent a letter to conductor Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony advocating for her work in the hopes that Koussevitzky would add one of her pieces to his program. These letters did not bear fruit, but the language Price uses in the beginning of her letter shows that she knew how her scores may be received:

To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins. Knowing the worst, then, would you be good enough to hold in check the possible inclination to regard a woman’s composition as long on emotionalism but short on virility and thought content;—until you shall have examined some of my work?

As to the handicap of race, may I relieve you by saying that I neither expect nor ask any concession on that score. I should like to be judged on merit alone—the great trouble having been to get conductors, who know nothing of my work (I am practically unknown in the East, except perhaps as the composer of two songs, one or the other of which Marian Anderson includes on most of her programs) to even consent to examine a score.[18]

While Price did write vocal music, and found much success doing so, she continued writing in idioms stereotypically considered to be “intellectual” like the symphony or string quartet. In doing so, Price is put herself in direct opposition with these harmful stereotypes, and demanded the musical establishment judge her by her work. In this context, the choice to title her string quartet Five Folksongs in Counterpoint is telling of Price’s uncompromising compositional identity considering, to Teal’s point, counterpoint was viewed as too “logical” to be considered feminine.

The final comparison to be drawn between Florence B. Price and Five Folksongs for Counterpoint is their virtual disappearance. Florence Price’s name does not grace the pages of many music history books including Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca’s A History of Western Music, Kyle Gann’s American Music in the Twentieth Century, or John Henry Mueller’s The American Symphony Orchestra: A Social History of Musical Taste, a book published the year Five Folksongs for Counterpoint was completed.

Much like Price herself, Five Folksongs for Counterpoint was forgotten for decades. The score was found in Price’s abandoned St. Anne, IL home, “strewn all over the floor” with other lost compositions that had gone unheard. [19]

[1] Florence Price, “ArchivesSpace at the University of Arkansas,” Collection: Florence Beatrice Smith Price Papers Addendum | ArchivesSpace at the University of Arkansas, accessed December 7, 2020, https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/1522.

The University of Arkansas bought the manuscripts from Price’s daughter in 2010. In 2018, it was announced that G. Schirmer had purchased the worldwide distribution rights of Price’s entire catalog. Among the formally missing pieces were Price’s fourth symphony, several orchestral works including Colonial Dance and Songs of the Oak, two violin concertos, and her Piano Concerto in One Movement.

[2] Mounir Nessim, “Five Folksongs in Counterpoint by Florence Price,” Mounir Nessim viola (Mounir Nessim viola, July 15, 2020), https://nessimviola.com/blog/five-folksongs-in-counterpoint-by-florence-price.

[3] Rae Linda Brown, Guthrie P. Ramsey, and Carlene J. Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020), 231.

[4] Rae Linda Brown has included this point in several of her writings on Price including her book The Heart of a Woman and the program notes she contributed to G. Schirmer’s publication of Price’s Sonata in E Minor for Piano. It is also mentioned in an article by Helen Walker-Hill, “Black Women Composers in Chicago: Then and Now,” Black Music Research Journal 12, no. 1 (1992). Several dissertations and theses have cited the use of spirituals including A Study of the Lives and Works of Five Black Women Composers in America by Mildred Denby Green (1975), A Stylistic Comparative Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Florence Price and Margaret Bonds by Meng-Chieh (Mavis) Hsieh (2019).

[5] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 128

[6] Ibid, 128

[7] Tim Sawyier, “Chicago Classical Review,” Chicago Classical Review RSS, September 5, 2019, https://chicagoclassicalreview.com/2019/09/florence-price-work-provides-a-highlight-with-nexus-chamber-music/.

[8] Meng-Chieh Mavis Hsieh, “A Stylistic and Comparative Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Florence Price and Margaret Bonds” (dissertation, n.d.).

[9] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 127

[10] James De Jongh, Vicious Modernism: Black Harlem and the Literary Imagination (New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

[11] Edward John FitzPatrick, “The Music Conservatory in America” (dissertation, 1963).

[12] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 56

[13] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 186

[14] Christopher Lebron, “The Invisibility of Black Women,” June 27, 2019, http://bostonreview.net/race-literature-culture-gender-sexuality-arts-society/christopher-lebron-invisibility-black-women.

[15] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 116-118.

[16] Jane M. Bowers and Judith Tick, “Passed Away Is the Piano Girl,” in Women Making Music: the Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), pp. 325-348.

[17] Ibid

[18] Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the Life and Music of Florence B. Price, 186

[19] Karen Tricot Steward, “After Lost Scores Are Found In Abandoned House, Musicians Give Life To Florence Price's Music,” KUAR, accessed December 16, 2020, https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/post/after-lost-scores-are-found-abandoned-house-musicians-give-life-florence-prices-music.

Berg, Gregory. 2013. "My Dream: Art Songs and Spirituals by Florence Price." Journal of Singing 69 (3) (Jan): 385-386. https://login.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/my-dream-art-songs-spirituals-florence-price/docview/1270666471/se-2?accountid=10920.

“Biography.” Florence Price. Accessed December 14, 2020. http://www.florenceprice.org/new-page-1.

Bowers, Jane M., and Judith Tick. “Passed Away Is the Piano Girl.” Essay. In Women Making Music: the Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950, 325–48. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Brown, Rae Linda. "Price [née Smith], Florence Bea(trice)." Grove Music Online. 30 Mar. 2020;

Accessed 24 Oct. 2020. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-90000367402.

Brown, Rae Linda, Guthrie P. Ramsey, and Carlene J. Brown. The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

Brown, Rae Linda. "The Woman's Symphony Orchestra of Chicago and Florence B. Price's Piano Concerto in One Movement." American Music 11, no. 2 (1993): 185-205. Accessed November 2, 2020. doi:10.2307/3052554.

Carter, Marquese. “The Poet and Her Songs: Analyzing the Art Songs of Florence B. Price,”

2018.

Cooper, Michael. “A Rediscovered African-American Female Composer Gets a Publisher.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 15, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/arts/music/florence-price-music-publisher-schirmer.html.

De Jongh, James. Vicious Modernism: Black Harlem and the Literary Imagination. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

Douglas Shadleon February 20, 2019. “Plus Ça Change: Florence B. Price in the #BlackLivesMatter Era.” NewMusicBox, February 20, 2019. https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/plus-ca-change-florence-b-price-in-the-blacklivesmatter-era/.

Ege, Samantha. "Florence Price and the Politics of her Existence.”." Kapralova Society Journal:

A Journal of Women in Music 16 (2018): 1-10.

Fabre Geneviève, and Michel Feith. Temples for Tomorrow: Looking Back at the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001.

FitzPatrick, Edward John. “The Music Conservatory in America,” 1963.

Hine, Darlene Clark, John McCluskey, and Marshanda A. Smith, eds. The Black Chicago Renaissance. Urbana, Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2012. Accessed December 8, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1hd18gg.

Hsieh, Meng-Chieh Mavis. “A Stylistic and Comparative Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Florence Price and Margaret Bonds,” 2019.

Howland, John. "Jazz Rhapsodies in Black and White: James P. Johnson's

"Yamekraw"." American Music 24, no. 4 (2006): 445-509. Accessed November 2, 2020. doi:10.2307/25046051.

Jackson, Barbara Garvey. "Florence Price, Composer." The Black Perspective in Music 5, no. 1

(1977): 31-43. Accessed November 2, 2020. doi:10.2307/1214357.

Lambert, John W. “The Price Is Right for Priceless as Florence Price Emerges from the Shadows at Duke.” CVNC, September 21, 2019. https://cvnc.org/article.cfm?articleId=9550.

Langley, Allan Lincoln. "Chadwick and the New England Conservatory of Music." The Musical

Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1935): 39-52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/738964.

Lebron, Christopher. “The Invisibility of Black Women,” June 27, 2019. http://bostonreview.net/race-literature-culture-gender-sexuality-arts-society/christopher-lebron-invisibility-black-women.

Maxile, Horace J. "Signs, Symphonies, Signifyin(G): African-American Cultural Topics as

Analytical Approach to the Music of Black Composers." Black Music Research

Journal 28, no. 1 (2008): 123-38. Accessed November 2, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25433797.

Murchison, Gayle. "Current Research Twelve Years after the William Grant Still

Centennial." Black Music Research Journal 25, no. 1/2 (2005): 119-54. Accessed November 3, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30039288.

“Music.com: Florence Price: ‘Five Folksongs in Counterpoint.’” Classical, November 11, 2018. https://africlassical.blogspot.com/2018/11/classical-musiccom-florence-price-five.html.

Nash, Jennifer C. “Re-Thinking Intersectionality.” Feminist Review 89, no. 1 (June 2008): 1–

15. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2008.4.

Nahum, Daniel Brascher. 1933. "Roland Hayes Concert shows Progress of Race in Music." The

Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 24, 11. https://login.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/historical-newspapers/roland-hayes-concert-shows-progress-race-music/docview/492352126/se-2?accountid=10920.

Nessim, Mounir. “Five Folksongs in Counterpoint by Florence Price.” Mounir Nessim viola. Mounir Nessim viola, July 15, 2020. https://nessimviola.com/blog/five-folksongs-in-counterpoint-by-florence-price.

Price, Florence. “ArchivesSpace at the University of Arkansas.” Collection: Florence Beatrice Smith Price Papers Addendum | ArchivesSpace at the University of Arkansas. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/1522.

Sawyier, Tim. “Chicago Classical Review.” Chicago Classical Review RSS, September 5, 2019. https://chicagoclassicalreview.com/2019/09/florence-price-work-provides-a-highlight-with-nexus-chamber-music/.

Smith, Bethany Jo. “Song to the Dark Virgin: Race and Gender in Five Art Songs of Florence B. Price,” 2007.

Steward, Karen Tricot. “After Lost Scores Are Found In Abandoned House, Musicians Give Life To Florence Price's Music.” KUAR. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/post/after-lost-scores-are-found-abandoned-house-musicians-give-life-florence-prices-music.

Walker-Hill, Helen. "Discovering The Music Of Black Women Composers." American Music

Teacher 40, no. 1 (1990): 20-63. Accessed November 3, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43542379.

Walker, Ryan Thomas. 2015. "Lessons in Musical Excellence: The Pedagogical Contributions of

George Whitefield Chadwick." Order No. 10131862, University of South Dakota. https://login.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/lessons-musical-excellence-pedagogical/docview/1810422312/se-2?accountid=10920.

A Spoonful of Levity Helps the Racism Go Down

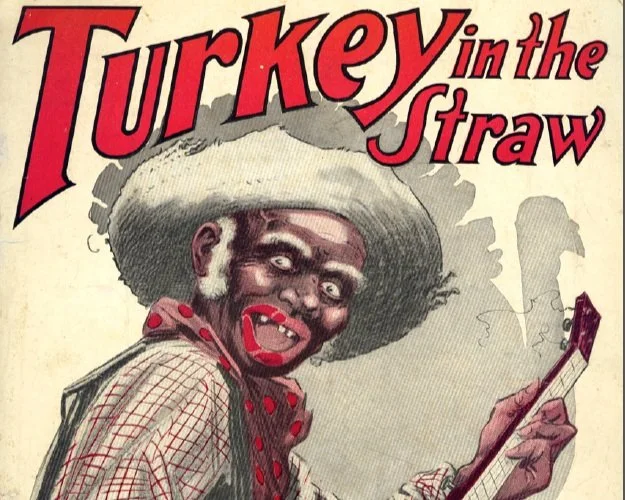

This post looks at the antebellum genre of "coon songs" that relied heavily on derogatory caricatures of African Americans for their content and performance. By presenting racist stereotypes in simple popular music forms, they helped keep racism and racist legislation palatable to American audiences.

T.D. Rice’s minstrel character, Jim Crow, was immensely popular from its inception in the 1820s. The character Jim Crow was instrumental in the popularity of minstrelsy as a form of entertainment and inspired countless songs and skits throughout the nineteenth century. Jim Crow – noted as the first stock character in minstrelsy – promulgated a stereotype of Black field hands being untrustworthy, shiftless, naïve, and boastful. Alan Green notes, somehow by combining blackness, rags, grotesqueness, song, dance, and dialect, ‘Daddy Rice’ had indeed fathered a universally-acceptable comic ‘Negro.’”[1] The legacy of the character continued as it became used as a derogatory term for Black Americans, and later the name became associated with various segregation laws in the United States.

Alongside Jim Crow on the minstrel stage was the city-slicking Zip Coon, created by George Washington Dixon. These two characters represented “two comic types which were to reign throughout the long career of Negro minstrelsy: the plantation or field-hand darky and the citified dandy.[2] Before the Civil War, the Zip Coon and other characters like him were created to make fun of freed African Americans who lived in the cities. Matthew Morrison described the Zip Coon as “the blackfaced urban dandy—attractive, well dressed, ‘educated’—effectively embodies the irony and fear of black ‘upward’ mobility throughout the nation, as he also performs the class frustrations of an urban, white working-class immigrant population on the rise between the 1820s and the 1840s.”[3] The Zip Coon has not had the cultural staying power of Jim Crow, but the impact of the character, the racist songs about him, and the racist songs he and Jim Crow would sing inspired decades of popular songs that spread and upheld racist stereotypes of Black Americans. In this paper, I investigate coon songs, a genre of comic songs popularized by blackface minstrelsy that developed into its own genre. The peak of the coon song’s popularity was about 1880 to the end of the First World War. In this paper, I will show how these songs furthered the spread of racist stereotypes, how they reflect racist ideology of the day, and how widespread its popularity was, reaching the height of American society. Furthermore, I will link these songs to the general attitude of many white Americans – as shown by legislation and writings of the time – towards Black Americans in the decades after the failure of Reconstruction.

The etymology of coon song, as with the Zip Coon, is linked to Black Americans being popularly associated with the raccoon. According to James Dormon, the association had nothing to do physical features, “but the association was largely by way of the ascribed affection of blacks for the amiable and tasty little beasts. By ascription, blacks loved hunting, trapping, and eating raccoons.”[4] Because of this association, the term “coon” became a racial epithet for African Americans. The term may have been further popularized by G.W. Dixon’s famous character, but that was not the genesis of the term. Zip Coon was not even the first known character named to reference raccoons. Andrew Barton’s 1767 The Disappointment; or the Force of Credulity includes a Black character name “Raccoon.”[5] Dixon’s Zip Coon, however, held much more cultural weight than previous characters, and is the titular character of a song that was influential on the coon song genre.

Popularity of coon song began to grow in the 1890s. However, by the end of the century the song form became an undeniable staple in American music and shows that did not include at least one coon song were doomed. As a writer for The Sioux City Journal noted in 1898:

Rising in popularity for about three years the “coon song” has almost swept away all competitors, says the Chicago Tribune. Scarcely a single song outside this classification has become popular within the last year. When the troops lay in the trenches around Santiago it almost seemed that “There’ll Be a Hot Time” had become our national anthem. A vaudeville show without a good “coon act” is as nothing now. A burlesque, according to the latest advices from New York, must be mostly a “black face” performance. Indeed, New York is reported to be quite mad on the subject. In the new Casino burlesque, for example, Miss Belle Davis sings “coon songs,” Miss Alice Atherton sings “coon songs,” Mr. Somebody Else, a “real coon,” sings “coon songs” […] The “real coon” is taking advantage of all this and is pressing hard the popularity of the “black face comedian” who is not the real thing. A team who only a few years ago were singing in a free show in Chicago are now getting one of the biggest salaries in the profession, and there is a story of a phenomenal jump from $35 a week to $350 made by another well known group of singers.[6]

This article makes clear the popularity of coon song, but also reveals that the American public writ large was interested in a more “authentic” portrayal of African Americans in public performance of coon song. Like the minstrel tradition that predated and gave birth to the musical genre, coon song offered a foot in the door for Black performers and songwriters to make a living in show business. This comparison has been made by other scholars who attempt to explain why Black actors, singers and songwriters willfully participate in their own denigration. Patricia Schroeder notes that beyond job opportunities, coon song writers – and minstrels before them – received benefits like “mobility, good pay, community status, and training in professional musicianship, all rare and valuable commodities for former slaves and the children of former slaves.”[7]

While the composition and performance of these songs may have led to upward mobility and fame for Black entertainers, it did not grant them immunity from American racism. On August 13, 1900, a police officer named Robert J. Thorpe died after he was stabbed by an African American man named Arthur Harris the night before. This triggered race riots and lynch mobs across the United States. A writer for the Birmingham Age-Herald wrote:

A mob of several hundred persons formed at 11 o’clock tonight in front of the home of Policeman Robert J. Thorpe… to wreak vengeance upon the negroes of that neighborhood because one of their race had caused the policeman’s death… in a few minutes the mob tonight swelled to 1,500 people or more, and as they became violent the negroes fled in terror into any hiding place they could find… The mob of white men, which grew with rapidity, raged through the district and negroes regardless of age or sex were indiscriminately attacked.[8]

Two weeks after this event, there were still rioters in New York. The Indianapolis paper, The Freeman wrote about Black entertainers being victimized by the mobs including Ernest Hogan, the composer of the famous coon song, “All Coons Look Alike to Me,”

The wild, uncontrollable passion of the mob was best shown on Broadway at 12:30 o’clock this morning, when that popular comedian and song writer, Ernest Hogan, was chased like a wild beast with a pack at his heels…

‘All Coons Look Alike to Me,’ Mr. Hogan’s own composition, had been rendered, to the applause of a large audience. Hogan, fashionably dressed, stood on the curb, twirling his cane.

A cry came from Forty-fourth street and Eight avenue, and a mob of five hundred men, armed with clubs and stones, surged over toward Broadway. Hogan was seen. ‘Get the [n-word]’ was the chorus. Hogan dropped his cane and started down Broadway on a run. The mob followed and for the next three minutes it had a life and death race for Hogan.[9]

As evidenced by this event, the upward mobility provided to Black artists could hardly be enough to justify coon song as a positive means of racial expression since the violence of racists could not be undone or avoided by these tunes. Additionally, the historic harm done by the genre far out-weighs the historic benefit. Beyond its being named after a racial slur, coon songs featured Black characters who were often portrayed as “foppish…, thieves, highly sexed, and violent.”[10] An article from 1906 published in the Kansas City Star notes, “There were hundreds of these songs and they treated of every variety of vice from the chicken-stealing, gambling, shiftless, gin-drinking, razor-fighting ‘[n-word].’”[11]

Looking into examples that portray African Americans as shiftless, the 1902 song “If Time Was Money, I’d Be a Millionaire” opens with the description of the song’s character as “a lazy coon a hangin’ round.” From there the first verse perpetuates the Jim Crow character of a Black American who is both lazy yet big and strong, which was used to imply natural ability of Black individuals for field work:

A lazy coon a hangin’ ‘round heard Parson Jenkins say

“Dat time was money” and it almost took his breath away

He never done a stroke of work he was too big and strong,

He’d stretch out in the boilin’ sun and sleep de whole day long

Of course he never had a dollar in his tattered clothes,

And didn’t own a pair of shoes to cover up his toes

De only thing he had was lots of time to pass away

An’ when he heard that time was money dis is what he did say[12]

This song also insinuates that this character is stupid and fundamentally does not understand the phrase “time is money.” The refrain of the song hammers this point in a way that leaves little to the imagination:

If time was money I'd be a millionaire

I’ve got time honey an’ chunks of it to spare

Oh dere ain’t no other coon could get wealthy half so soon

If time was money I’d be a millionaire[13]

In the second verse, Felix F Feist is more aggressive with his language – using the n-word twice – and asserting this man’s laziness in every line, saying:

Dis [n-word] was too lazy fo to raid a chicken roost

Because he’d have to lift his arm to give his hand a boost

He nearly starved to death one day fo’ certainly because

Didn’t have the energy to move his lazy jaws

Dis coon was never sociable it tired him to talk

If twenty mules would kick him all at once he wouldn’t walk

‘an so a baskin’ in the sun dis [n-word] laid all day,

A grinnin’, chucklin’ to himself an’ dis am what he’d say

The use of the n-word in the second verse of “If Time Was Money” caught the attention of a writer for the Indianapolis paper, The Freeman who noted,

Felix F. Fiest, a white man, author of the words to the coon song, “If Time was Money” has used the word “n-word” in the second verse of his song. I find the word… to be common place and not appreciated by the best classes of people. There seems to be no objections to the word “coon” and the word “darkey” could easily be substituted.”[14]

Elsewhere in the article, the author notes “music publishers took a trip abroad last winter in search of a substitute for the ‘coon’ song… In the meantime, Jos. W. Stearn’s music company has consumed all the famous song writers in New York… to flood the market with genuine coon songs.” The two quotes show that this author does not take as much issue with the practice of writing such offensive songs (though the article mentions a publisher who refuses to write them), but does take issue with the language of certain tunes, showing that even for the Black press, racism in music is not completely unacceptable provided the songwriters use more admissible racist nomenclature. Furthermore, it is not bothersome or worth mentioning in the article that the mere premise of the song is perpetuating racist stereotypes and portraying a Jim Crow-like character that is so lazy he would starve to death since he cannot bring himself to chew. At this point, however, the premise of racist song themes was so commonplace that it would not be noteworthy since it was simply part of the song form.

“If Time Was Money” was not the only song that leaned on the trope of racialized laziness and relating it to economic misfortune. Two other examples of this stereotype were both written in1898 song: “I Wish My Rent Was Paid,” and “I’m Having a Million Dollar Dream.” “I Wish My Rent Was Paid,” begins: “A group of coons one day / Was a wishin’ their time away / They were wishin’ for wealth, and a-wishin for health / And a-wishin’ they could get more pay.” “I’m Having a Million Dollar Dream” begins by describing a character, Bill Jackson as “a lazy coon, as lazy as could be / I never seen such worthless loon since coons were first set free.” All three of these songs portray African Americans as both obsessed with being rich as well as unwilling or unable to work to make money. The latter two songs describe lazy, day-dreaming dead beats before adding stanzas about how they go find jobs and are then unsuccessful. The writing of characters too lazy to lift a finger, who then find work but are not financially rewarded is an antinomy within the stereotype. African Americans are seen as simultaneously too lazy to earn any money and too stupid to keep the money they earn from working – ultimately making them unfit to do business in the eyes of white Americans.

Alongside being portrayed as lazy, African Americans were also often portrayed as violent. The threat of violence was most often signified with a character wielding a razor. Sometimes the reference is in the title like the 1885 song, “De Coon Dat Had De Razor,” or it could be worked into the song for the sake of mentioning a razor. The song “Armazindy Lee” is a love song in which the point of view is a man singing about the woman he wants to marry. In the second verse while talking about the wedding ceremony, the songwriter Eugene Todd includes the line, “Of case there is a fight in the middle of the night / why you’d better have a razor up your sleeve.”[15] Additionally, some songs portrayed a dangerous character like the 1896 song, “Bully Song,” which includes these starting lines for the two verses:

Have yo’ heard about dat bully dat’s just come to town

He’s round among de [n-words] a layin’ their bodies down

I’m a lookin’ for dat bully and he must be found

I’m a Tennessee [n-word] and I don’t allow

[…]

I’s gwine down the street with my ax in my hand

I’m lookin’ for dat bully and I’ll sweep him off dis land

I’m a lookin’ for dat bully and he must be found

I’ll take ‘long my razor, I’se gwine to carve him deep[16]

This song sticks tightly to the theme of violence, making sure in the second verse to reference the protagonist’s weapons: an ax and a razor. These songs amplify the notion that African Americans are violent and to be feared. If their laziness was justification to exclude them in business, the violence was a justification to keep African Americans at arm’s length socially.

Coon songs were written as comedy songs, but the stereotypes they spread had very real and unhumorous consequences. Notions that African Americans were inherently violent, stupid, lazy, and more sexually deviant than white Americans were not just littering the pages of coon song but represented widespread American thought. These stereotypes had an influence on business practices, social dynamics, scientific theories, and legislation. Moreover, the legislation birthed out of insidious American racism further impacted the social and business lives of African Americans.

Outside of the context of music and theater, coon song is used as a pop culture reference for American racists. Coon song was referenced in a 1903 poem sent into the Belleville News Democrat by a reader who was furious that President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington over to the White House for a dinner two years prior. The poem entitled “[N-words] in the White House” begins with, “Things in the White House / Looking mighty curious / [N-words] running everywhere / White people furious.”[17] The fourteen-stanza poem is penned by “Unchained Poet in Democrat Leader, Missouri,” who primarily complains that Black men have been allowed to step foot inside the White House with passages like:

[N-words] on the front porch

[N-words] on the gable

[N-words] in the dining room

[N-words] at the table

The poem also advocates beheading the president as well as including references to African American music styles like the cake walk and coon song:

[N-words] in the sitting room

Making all the talk

[N-words] in the ball room

Doing cake walk

[N-words] in the east room

Make a might throng

[N-words] in the music room

Singing a coon song

The song references these two popular forms of entertainment along with playing craps, plundering, and “raising hell” as though these are strictly activities and forms of entertainment enjoyed by African Americans. As noted, however, coon songs were first written by white entertainers, reflecting white perception of African Americans more than reality. The vitriol for African Americans being spewed across the pages of the Belleville News Democrat shows themes found in coon songs were not innocent fun or light-hearted jabs, they were heart-felt sentiments for a substantial number of Americans around the start of the twentieth century. These racist beliefs are being reinforced with every new song being heard, as listeners ingest another spoonful of racism every time the gather around the piano. This happened often, as coon song’s popularity was so immense that in 1898 an article was written about President William McKinley’s acceptance of the genre.

In the Afro-American Sentinel titled “McKinley’s Musical Tastes,” President McKinley is portrayed as a pious, hymn-singing man who enjoys listening to opera. The article’s subheading, “The President Has Succumbed to the ‘Coon Song’ Craze,” is addressed laying affirming the president’s high-brow taste, saying that the president does not “despise the modern songs of light opera and the vaudevilles.”[18] The article notes that McKinley was delighted to have singer Kate Huntington serenade him with the song “Louisiana Lou.” The lyrics are not as overtly racist as songs like “If Time Was Money, I’d Be a Millionaire” or the myriad of other songs that portray African Americans as lazy, violent, and oversexed. However, the lyrics are still bursting with mimicry of “Black” dialect. For instance, the refrain of the piece is written:

Lou, Lou, I lub you; I lub you, dat's true

Don't cry, don't sigh, you'll see me in de mornin'

Dream, dream, dream ob me, and I'll dream ob you

My Louisiana, Louisiana, Louisiana Lou

The refrain is filled with the typical trappings of apparent Black dialect often found in coon song: “d” replaces “th” as in “dat’s true,” “b” replaces “v” and “f” as in “I lub you” or “dream ob me.” These linguistic mannerisms are carried over from the minstrel caricatures of African Americans like Jim Crow or Zip Coon. The use of faux “Black” dialect was the most universal stereotype in coon song and is included in the very definition of the genre provided on Grove Music Online.[19] The acceptance of the stereotype by McKinley, who was voted into office with the expectation that he would be as progressive as other Republicans of the time, exemplifies how normalized these stereotypes were by the end of the nineteenth century.

Stereotypes found in coon song proved to be most harmful in the creation of legislation. In the early days of minstrelsy, the perceived lazy plantation-dwelling enslaved Jim Crow and well-dressed yet undignified city-dwelling dandy Zip Coon were created to poke fun at African Americans. These portrayals primarily made African Americans look foolish and lazy. However, in the decades following emancipation, violence became a more significant theme and the laziness amplified to paint newly freed African Americans as both inferior and threatening. Notions of white superiority and fear were used to rationalize laws meant to keep white people as distanced from African Americans as possible.

In 1875, congress passed the Civil Rights Act which stated:

That all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude. [20]

In 1883, about the year that “the fad [of coon songs] had its origins,” the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act was called to question and swiftly nullified by the United States Supreme Court.[21] This made it possible for states to enact laws that kept African American passengers separated from white passengers on public conveyances like steamboats, train cars, and busses – which many states adopted during the heyday of coon songs. Part of the justification for racial separation on public transit was the perceived threat to white people. This perception was fueled by ideas seen in coon songs as Phillip Bruce makes clear in his 1911 article when he justifies segregating train cars:

The white people… demanded the change [to double accommodations in order to separate by race], and the railways offered no serious opposition. A more useful law was never inserted in the Southern statute book. No one who remembers the former promiscuous commingling of whites and blacks in the Southern trains can fail to recall the scenes of violence witnessed there in consequence of the aggressive attitude of negroes inflamed by drink. [22]

The duel stereotyping of African Americans as both lacking intelligence and averse to work ethic resulted in their being treated as a truly inferior race of people. This was compounded by scientific racists who espoused the view that “innate physiological and biological differences [that] separated the races.”[23] This resulted in extremely condescending views of African American’s role in American society. William Starr Myers claims “the negro must be recognized as one of an inferior, not merely a backward, race. He must be treated as a ‘grown-up child’ – with justice, but with authority. He must be educated and given every opportunity to develop to the limit of his capacity.”[24] He then minimizes the achievements of any African Americans and marginalizes their place in society as a helper to the white establishment by saying, “a few of the thoroughly capable negroes (and their number is pitifully small) should be educated above the average of their fellows to aid the whites in leading their people.”[25] Philip Bruce echoes the presentation of African American intellect in coon song in his reasoning for treating them as second class citizens, saying:

In rushing in and arbitrarily and prematurely requiring the South to enfranchise the indigent and illiterate black man almost as soon as he had obtained his freedom, the North dislocated hopelessly for a time that judicious evolutionary process through which negro suffrage would have passed, had the Southern people been left to confer that right gradually and to regulate its exercise.[26]

Negative stereotypes that were reinforced by coon song did incalculable damage to the ways in which African Americans were perceived, as evidenced by the way in which writers present Jim Crow laws as ways to preserve Southern (white) society as well as to protect the apparently helpless (but also overly violent) African Americans during their process of social evolution. Preserving Southern society is central to Philip Bruce’s article:

The most notable achievements of this constructive local statesmanship consist of five great enactments, namely, the practical disfranchisement of the negro, the prohibition of the intermarriage of the races, the interdiction of their co-education, their separation in all public conveyances, and their domiciliary segregation in the cities.[27]

The racist drivel found throughout the coon song genre showed a sort of fascination with African American culture. Not an accurate depiction of African American life, but a construction of Blackness created by white Americans – a construction that would allow for the continued oppression of a formerly-enslaved group of people. The construction of race and racial stereotyping in the United States is still not completely solved more than fifty years after the end of segregation and over one hundred years after the popularity of coon songs died out. Coon songs started to fade away in the early 1900s with articles marking the end of the genre appearing throughout the latter half of the aughts. In 1906, a white-owned newspaper, The Kansas City Star published an article titled “’Coon Songs’ on the Wane: The Rapid Rise and Decline of ‘Rag Time’ Music” in which they gleefully declare that the sun is setting on coon songs and its parent genre ragtime:

The American public have renounced the “coon song” with its negro “rag time” Probably no fad in the musical world ever took hold of the popular fancy with a more tenacious or longed-lived grip than the “coon” song… The public mind was saturated with it…

About three years ago the popularity of the rag-time song began to wane and it has been rapidly approaching the extinction since then. It isn’t quite dead, of course. Once in a while somebody has the heartlessness to hammer out a rag-time “selection” on the piano. But hardly anybody composes one nowadays.[28]

The article continues its obituary for ragtime and coon song, lamenting that such annoying music has remained in the public sphere for nearly two decades. Not once, however, does the author cite the racist lyrics as a reason to celebrate the genre’s demise. Rather, they are more interested in the quality of the lyrical structure and repetition of themes than the message of the genre. An African American-owned newspaper, The Freeman, on the other hand, published an article in 1909 entitled “’Coon’ Songs Must Go” in which they lambast the laziness of lyricists who rely on tired stereotypes to sell a song. This lengthy article dissects how damaging the music is for African Americans, how African Americans participated in their own denigration, and notes how the repeated use of racial epithets in songs started as fun but did not stay tethered to the music.

Coon songs, after the great damage they have done to the American colored man are now dying out. Although “rag” time melody may live forever, the words “coon,” “[n-word]” and darkey are now being omitted by song writers. Usually some fictitious name as “Sam Johnson” and “Linda Lue” are used in the lines of poetry instead of the word “coon” which is very offensive to the colored race and makes the hair raise on their heads when they hear it. There is a great difference in composers of 20 years ago to the later day poets… Nowadays the composers have no respect for good people, no thought of elevating, careless of hurting good innocent people’s, they rush their horrible junk on the market for sale. Out for graft they use slang hurried-up poetry – anything that will sell quickly. The colored writers not knowing the harm they were doing took a stick to break their own hands by writing “coon” songs.

[…]

Williams & Walker are a great deal to blame for being the originators and establishing the name “coon” upon our race… In order to achieve success or to attract the attention of the public they branded themselves as “the two real coons.” Their names accompanied with “coon” songs was soon heralded… As much as to say the Negro has now changed his name. He is no more human, but a “coon.” [Williams & Walker and Ernest Hogan] needed the money, what little they received, and the white people needed the laugh on the ignorant… Colored men in general took no offense… and laughed as heartily on hearing a “coon” song as the whites. But where the rub came is when the colored man was called a “coon” outside of the opera house. Instead of the whole race raising up in arms and protesting against such slang used in songs and such horrible caricatures on the title pages, they good naturedly joined in the chorus “All Coons Look Alike to Me.”[29]

Additionally, the author discusses the effects on children hearing the casual racism of coons songs.

Every colored man and woman of any pride, whether educated or not, becomes grossly insulted when called a “coon.” Yet he can’t go to a theatre nor listen to a phonograph without being told that he is a “coon.” The name “coon” in a song we understand is only meant… to amuse or to cause laughter while you play the song… but it don’t stop there. A show goes to a country town – some low down, loud-mouth “coon shouter” sings “Coon, Coon, Coon” or some other song… with an emphasis on the word “coon.” Then the people, especially the children are educated that a colored man is a “coon.” What was meant for a jest is taken seriously. [30]

The legacy of the coon song is summed up well in the sentiment that it was a jest taken seriously. However, in the wake of the Civil War along with the rise and fall of reconstruction, it is more likely that coon song was never truly jest. The hatred that filled the pages of hundreds of song books represented real resentment that had festered in primarily Southern whites since the end of the war. By repeating heinous phrases with a laugh and a smile, racism could be made more palatable for white audiences who took little pushing to hop on board, as well as African American audiences.

[1] Green, Alan W. C. “‘Jim Crow,’ ‘Zip Coon’: The Northern Origins of Negro Minstrelsy.” The Massachusetts Review 11, no. 2 (1970): 385–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25087995.

[2] Ibid, 390.

[3]Matthew D. Morrison, “Race, Blacksound, and the (Re)Making of Musicological Discourse,” Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 72, no. 3 (2019), 81-823. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2019.72.3.781.

[4] James H. Dormon, “Shaping the Popular Image of Post-Reconstruction American Blacks: The ‘Coon Song’ Phenomenon of the Gilded Age, American Quarterly, Vol. 40, no. 4 (December 1988), 452

[5] Ibid, 451.

[6] "In the Theatrical World the Dramatic Season in Sioux City in New in Full Sway." Sioux City Journal (Sioux City, Iowa), September 4, 1898: 5. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A11A8291E9BB54EB8%40EANX-11B5CA0A379EA5C0%402414537-11B5CA0A68056C20%404-11B5CA0B295C8810%40In%2Bthe%2BTheatrical%2BWorld%2Bthe%2BDramatic%2BSeason%2Bin%2BSioux%2BCity%2Bin%2BNew%2Bin%2BFull%2BSway.

[7] Patricia R. Schroeder, “Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race,” Wiley Online Library (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, June 9, 2010), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1542-734X.2010.00740.x,143.

[8] "New York Mob after Negroes Repetition of the Recent Riot in New Orleans. Many Blacks." Age-Herald (Birmingham, Alabama), August 16, 1900: [1]. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A11EC25AD467AEC15%40EANX-11F4787A26D6C3A8%402415248-11F4787A30408A00%400-11F4787A6E1276D0%40New%2BYork%2BMob%2Bafter%2BNegroes%2BRepetition%2Bof%2Bthe%2BRecent%2BRiot%2Bin%2BNew%2BOrleans.%2BMany%2BBlacks.

[9] "Stage." Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), September 1, 1900: 5. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANX-12C8A2616CAAF3A8%402415264-12C8A261A1BF5010%404-12C8A2625527F460%40Stage.

[10] Neal, Brandi A. "Coon song." Grove Music Online. 16 Oct. 2013; Accessed 10 Dec. 2021. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002249084.

[11] "'Coon Songs' on the Wane. The Rapid Rise and Decline of 'Rag Time' Music." Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Missouri), March 4, 1906: 13. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A1126152C152E4978%40EANX-11650C30B0520690%402417274-11650C34C55F6590%4038-11650C43C3C86A10%40%2522Coon%2BSongs%2522%2Bon%2Bthe%2BWane.%2BThe%2BRapid%2BRise%2Band%2BDecline%2Bof%2B%2522Rag%2BTime%2522%2BMusic.

[12] Felix F. Feist, If Time was Money, I’d be a Millionaire, 1902

[13] Feist, 1902.

[14] "Professional Philosophy." Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), July 19, 1902: [5]. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANAAA-12C4F968687037F8%402415950-12C4F968964ADD08%404-12C4F96979992DA0%40Professional%2BPhilosophy.

[15] Armazindy Lee,

[16] Bully Song

[17] "Poetry," Belleville News Democrat (Belleville, Illinois), July 25, 1903: 2. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A114CEEB0320B0130%40EANX-11532DC0A49130D8%402416321-11532DC126037DB8%401-11532DC24D9B8928%40Poetry.

[18] "McKinley's Musical Tastes. The President Has Succumbed to the 'Coon Song' Craze." Afro-American Sentinel (Omaha, Nebraska), February 5, 1898: 1. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B9767335867038%40EANAAA-12CE2CDC1312D7D0%402414326-12CC42BC041E1F78%400-12EA3C091ACE8C80%40McKinley%2527s%2BMusical%2BTastes.%2BThe%2BPresident%2BHas%2BSuccumbed%2Bto%2Bthe%2B%2522Coon%2BSong%2522%2BCraze.

[19] Neal, “Coon Song.”

[20] Stephenson, Gilbert Thomas. “The Separation of the Races in Public Conveyances. The American Political Science Review. (1909):180-204.

[21] "'Coon Songs' on the Wane. The Rapid Rise and Decline of 'Rag Time' Music." Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Missouri), March 4, 1906: 13. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A1126152C152E4978%40EANX-11650C30B0520690%402417274-11650C34C55F6590%4038-11650C43C3C86A10%40%2522Coon%2BSongs%2522%2Bon%2Bthe%2BWane.%2BThe%2BRapid%2BRise%2Band%2BDecline%2Bof%2B%2522Rag%2BTime%2522%2BMusic.

[22] Philip Alexander Bruce, “Evolution of the Negro Problem,” in The Sewanee Review 19, No. 4 (1911), 392

[23] Andrea Patterson, “Germs and Jim Crow: The Impact of Microbiology on Public Health Policies in Progressive Era American South,” in Journal of the History of Biology 42, no. 3 (2009), 530

[24] Wm. Starr Myers, “Some Present-Day Views of the Southern Race Problem,” in The Sewanee Review 21, No. 3 (1913), 348

[25] Ibid., 348.

[26] Philip Alexander Bruce, “Evolution of the Negro Problem,” in The Sewanee Review 19, No. 4 (1911), 387

[27] Ibid, 386

[28] "'Coon Songs' on the Wane. The Rapid Rise and Decline of 'Rag Time' Music." Kansas City Star

[29] Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), January 2, 1909: [5]. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANX-12C55FDC3692A460%402418309-12C55FDC927A4920%40.

[30] Ibid.

The Performance of Outrage Over Black Androgyny

This post looks into the reception of Prince and Grace Jones, artists that blurred or defied gender norms, and ways in which their blurring of gender binaries has been received as distasteful. Rather than concentrate on how these artists embody androgyny, the aim of this paper is to show how critics (professional or armchair) essentialize artists as distasteful. This is the first time in my research that I rely on anecdata in the form of reviews on sites like Amazon and IMDB. Leave a comment and let me know what you think.

In this post, I consider reception of the ways in which Prince and Grace Jones blurred or defied the norms of gender performance, with an aim to explain visceral reactions of their androgyny. In this paper, I examine the reception of nonheteronormative musicians, how they have been viewed as distasteful, and explore the visceral reactions and the embodiment of disgust displayed by their critics. I first give a brief overview of androgyny, and analyze the performance of androgyny in the work of Prince and Grace Jones after which visceral negative criticism of their androgyny is presented, and the embodiment of these reactions is discussed.

The term androgynous is defined by the AACRAO as Identifying and/or presenting as neither distinguishably masculine nor feminine.[1] Androgyny is being used over terms like bigender, nonbinary, gender fluid, and genderqueer since androgyny does not necessarily relate to gender identity and can be used to refer to both Prince and Grace Jones. Focusing on the embodiment of androgyny and the critical reception of androgynous artists, it is necessary to discuss the performativity of doing gender. Given the nature of their professions as entertainers, Prince and Grace Jones have been spoken of as performing gender or androgyny. In Undoing Gender Judith Butler discusses the social inclination to conform to constructions of gender as a way of belonging, but suggests a kind of spiritual rightness in maintaining one’s ambiguity,

There are advantages to remaining less than intelligible, if intelligibility is understood as that which is produced as a consequence of recognition according to prevailing social norms. Indeed, if my options are loathsome, if I have no desire to be recognized within a certain set of norms, then it follows that my sense of survival depends upon escaping the clutch of those norms by which recognition is conferred. It may well be that my sense of social belonging is impaired by the distance I take, but surely that estrangement is preferable to gaining a sense of intelligibility by virtue of norms that will only do me in from another direction. Indeed, the capacity to develop a critical relation to these norms presupposes a distance from them, an ability to suspend or defer the need for them, even as there is a desire for norms that might let one live.[2]

Prince Rogers Nelson was a prolific singer, songwriter, guitarist, and producer who is often regarded as one of the most talented and influential musicians of his generation. Prince self-produced and recorded his debut record, For You, for Warner Bros. Records when the artist was 19 years old.[3] For You was the first of nearly forty studio albums Prince would release under his own name over the course of his life. Prince increased his creative output by forming several other side projects, notably The Time (AKA Morris Day and The Time), for which he would write the music and perform the instrumental parts on records. Michael Wells penned an early writeup of Prince for the New York Amsterdam News in which he said, “I can sum up the totality of Prince in two words, musical genius. On his debut album, For You, he played twenty-seven instruments and sang all lead and background vocals.”[4] Throughout his career, Prince was often noted for his musical mastery as well as his sexuality and his ambiguous performance of gender. In the very same article, Wells describes the masculinity and femineity of his vocal performances, asking readers, “Can you imagine a voice that is a mixture of Minnie Riperton, Smokey Robinson and Robert Plant? No! Well that’s what kind of voice God has blessed Prince with.”[5] This vocal performance is one of myriad of way that Prince, “denie[d] himself and his audience the luxury of an intelligible gender,” and “altered and transcended the culture in the 80s and 90s by regularly wearing make-up and women’s clothing – yet was considered a hetero-sex icon.”[6]

Several critics in the early 1980s noted his falsetto voice as well as the sensuality of his performances. In another article printed for New York Amsterdam News, Gene Gillis writes about the crowd’s frenzy over Prince’s sexuality. Interestingly, beyond the use of male pronouns for Prince, the description of the artist’s sensuality and the reaction by the crowd does not contain many gender descriptors:

This is the only time the crowd really got a chance to see Prince’s body, as he took off his shirt, and set off a giant roar from the crowd as they were expecting to see more and he teased them as he unzipped his pants and toyed with his little black bikini, to the roar of the crowd’s ‘take it all off’ which he did not do… He would take his guitar, stroke and lick it at the same time while making sexual gestures on the long end of the instrument with his hands.[7]

Not every critic wrote so favorably of Prince’s performances at the time. The very same month as Gillis’s review, The New York Times printed a review that read:

Prince, the Minneapolis-based funk-rock star who appeared at the Palladium on Wednesday, appears to have reached a delicate crossroads in his career. Having achieved notoriety for his racy songs and flamboyantly erotic performing style. Prince has embraced controversy for its own sake.

His latest album addresses political and religious issues with the same simplistic bravado that he used to devote solely to sexual matters.[8]

The album referred to in the New York Times review was his fourth record, Controversy. The opening lyrics of Controversy’s title track addresses the reception of Prince’s sexual performances, specifically noting the perceived ambiguity of his race and sexual orientation

I just cant believe all the things people say – controversy

Am I black or white, am I straight or gay? – controversy[9]

This would not be the first time Prince alludes to ambiguity in his lyrics. As other scholars have noted, Prince references his androgyny more directly in the opening lyrics to his hit “I Would Die 4 U, stating,”

I’m not a woman, I’m not a man

I am something that you’ll never understand[10]

Prince was revered and reviled for his androgyny, which appeared not only in his lyrics and the performance of his music, but in his wardrobe on and off stage as well as his interview performativity. Shortly after Prince’s death, Slate published a story that read, “few could claim to fully grasp Prince’s easy embodiment of both maleness and femaleness. His schooled evasion of conventional classifiers made him endlessly fascinating.”[11] One of his earliest on-camera interviews exemplifies this fluid performance of gender and shows Prince’s sense of humor as he plays off of the perception of his persona. During the interview, Prince is asked “some people have criticized you for selling out to the white rock audience with Purple Rain and leaving your black listeners behind; how do you respond to that?” after which Prince yells “Come on, come on,” clears his throat, stares down the barrel of the camera, and pitches his voice higher to exclaim, “cufflinks like this cost money, okay. Let’s be frank, can we be frank? If we can’t be nothing else then we might as well be frank, okay?” He proceeds to blow kisses at the camera before lowering the pitch of his voice to say,

seriously, I was brought up in a black and white world… I listened to all kinds of music when I was young, and when I was younger, I always said that one day I was going to play all kinds of music and not be judged by the color of my skin, but the quality of my work.[12]

The effeminate diva response to the initial question was being played for laughs, but it shows a sort of ease Prince possessed of code switching between masculinity and femineity in vocal performance. The facet of Prince’s androgyny that received the harshest criticism and the most overt displays of hate was his sense of fashion. From the start of his career, Prince challenged gender norms with his stage attire. During his 1981 tour promoting the album Dirty Minds, “Prince, dressed like his album cover—long coat, red handkerchief around his neck, his hair cut in punk rock style, black leg warmers and little black, bikini-style briefs.”[13] This was Prince’s stage attire when he and his band opened for The Rolling Stones, causing a contemptuous reaction from the predominately white audience as a 1981 Chicago Tribune article states:

How rigid are racial categories in contemporary pop music? Prince recently found out when The Rolling Stones invited him to open several West Coast concerts on their 1981 tour. The suggestions of androgyny in his fluid body movements and flamboyantly minimal stage costume were more than a little reminiscent of some of Mick Jagger's early performances, but the almost entirely white stones audience apparently failed to make the connection. They pelted Prince with fruit and bottles, causing him to cut his sets short.[14]

The writer stresses displays of disgust from the Rolling Stones audience is not just due to the sight of an androgynous artist, after all Mick Jagger was wearing dresses and eye makeup a decade before Prince had. What sparked such explosive reactions was black androgyny; an otherness that the crowd deemed unacceptable. Not all of Prince’s “othering” by the press spectators was so overt. Furthermore, Prince’s displays of androgyny were also not always so overt.

An example from the height of his popularity of blurring gender lines is the movie Under the Cherry Moon, a film that has been jokingly described as “a film noir in which Prince is the femme-fatale.”[15]: Under the Cherry Moon was written by, directed by, and starred Prince, so his presentation was in his complete control. The film begins with a narrator setting scene and identifying the protagonist, Christopher Tracy [Prince], as a “bad boy” and womanizer:

Once upon a time in France, there lived a bad boy named Christopher Tracy . Only one thing mattered to Christopher. Money. The women he knew came in all sizes, shapes, and colors, and they were all rich. Very rich. Private concertos, kind words, and fun is what he had to offer them. Yes, Christopher lived for all women, but he died for one. Somewhere along the way, he learned the true meaning of love.[16]

Figure 1: Stills of Prince in Under the Cherry Moon wearing a jacket that from the front resembles a men’s suit, but from behind shows the back exposed in a way more common of women’s clothing.